Privacy isn’t dead, no matter what anyone tells you

But AI and Big Tech are doing their best to exterminate what's left of it

AI has its eyes on you. Source: DALL-E.

I recently got an email from a new subscriber, reacting to my last Substack column about AI’s disturbing ability to invade your personal privacy without being asked. It read:

Dear Cranky:

Is it a mistake for me to think I'm "safe" because I have nothing to hide? Anyone willing to pay a few bucks can get most of my info from the interwebs…. Am I being too naive?

Hugs,

LVT

When people say this to me (and LVT is hardly the first), I usually respond, “You have nothing to hide? Excellent. Now drop your pants and hand me your credit cards.”

If people really had nothing to hide, we’d all be walking around naked, with our bank routing numbers tattooed on our foreheads.

I think what LVT really means is, “I’ve done nothing wrong.” Or perhaps, “I’ve done nothing that would cause me harm if it were broadcast on the Six O’clock News.”

Kent Brockman, reporting from the deepest crevasses of your psyche. Source: Vents Magazine.

But that’s different than declaring your life an open book, free for anyone to rummage through. And that’s where a lot of people get privacy wrong.

ICYMI: Don’t spy on me

Privacy is not about hiding information you’re ashamed of. It’s about deciding who gets to know what. Your doctor does not need to see your tax returns. Your accountant does not need to know the results of your colonoscopy. There are things you’d tell your best friend that you’d never tell your spouse, and vice versa. It’s about context, and about choice.

And you should be the one who gets to decide.

Of course, there are some things you don’t have control over, because they’re encoded in law. Property records, for example, are public. So are most criminal records. There are good reasons for this. You don’t want someone running for mayor to hide the fact she’s been arrested for murder. You want to know if the land the city has just acquired for significantly more than its actual value is owned by her brother in law.

ICYMI: Your AI in the sky

Unfortunately, this public information – collected and stored using your tax dollars – has become a commodity sold by skeezy information brokers. That, coupled with our compulsion to overshare on social media, and Google’s frankly amazing ability to find all that information and serve it to you in milliseconds, has led to the belief that nothing is private any more.

But it isn’t true. At least, not yet.

“You have zero privacy anyway. Get over it.”

That statement was made in 1999 by then-CEO and founder of Sun Microsystems, Scott McNealy. It’s been widely quoted ever since. [1]

You know who’s privacy is still significantly higher than zero, 24 years later? Scott McNealy’s.

There are plenty of other people (nearly all of them beneficiaries of the information-sharing economy) who’ve said something similar, but just for fun, let’s pick on Scott.

McNealy has an extensive Wikipedia entry, which details his accomplishments, work history, and support of Donald Trump’s presidency, among other things. He has a net worth of between $1 billion and $1.5 billion, depending on the source. His son, Maverick, is a pro golfer on the PGA tour, and he has three other adult children named Colt, Dakota, and Scout.

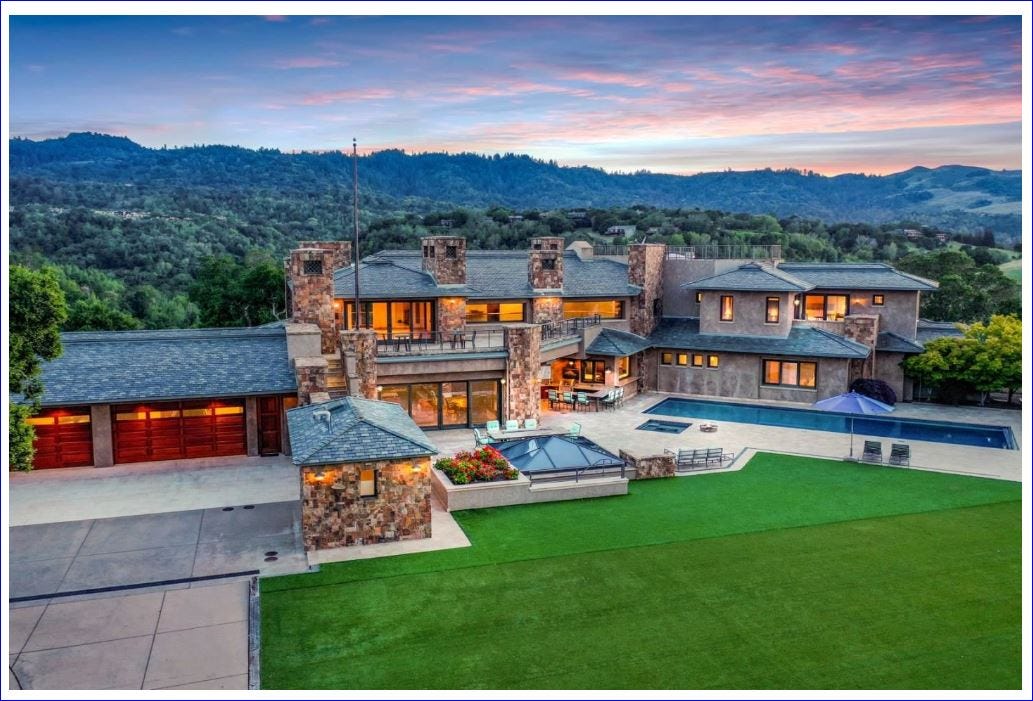

He’s been trying to unload his 13,000 square foot mega-mansion in Portola Valley for the past three years, without success. But not to worry; he also maintains homes in Las Vegas, Palm Springs, Pebble Beach, and elsewhere.

Five bedrooms, eight baths, 21,000+ square feet – a steal for just $54 million, marked down from $96 million.

There’s a lot to know about Scott. He’s a very public guy, and he loves attention. You can tell by how often he’s been quoted in the media.

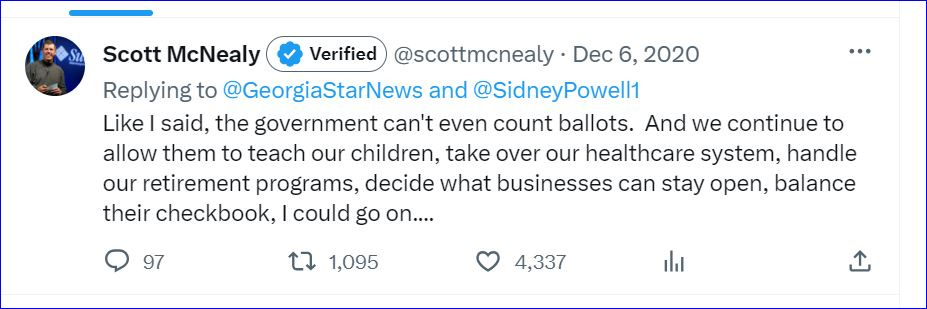

He’s also got this Tweet pinned to the top of his Xitter profile:

I wonder if The Kraken asked him for bail money.

All of this is available via a free Google search. I even paid $27 to one of those bullshit people search sites for a complete scan of his records, but it turned up even less information than Google. [2]

Try as I might, however, I still cannot locate Scott’s bank account information, tax returns, the results of his last checkup, or any food allergies he might have. I don’t know what medications he takes, or if he suffers from depression or anxiety or narcissistic personality disorder. I don’t know what books he reads or podcasts he listens to. I don’t know what he’s watched on Netflix or bought from Amazon. I don’t know the name of his high school sweetheart or his best friend. I know he owns multiple homes, and I’m pretty sure he still has a private jet, but I have no idea where he is at any given moment.

I don’t know if McNealy has ever been arrested or gotten a speeding ticket. [3] I don’t know if he’s hiding money from the IRS in some floating tax haven. I know he’s married, but I don’t know if he’s got a mistress or what kind of kink he/they are into. I don’t know if he’s plagued with self doubt. But given that he describes himself as a “raging libertarian,” I sincerely doubt it.

Fortunately, it didn’t. Source: Peoplewhiz.

I don’t even know what he did last summer. (Though I’m pretty sure he played golf.) In short, I know what Scott wants me to know – and little else.

Sounds pretty private to me. [4]

None of their beeswax

Instead of being dead, privacy has actually been making a comeback in recent years. Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), passed in 2018, puts real limits on what companies can do with your personal information. California’s Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and Consumer Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) are having a similar impact on US organizations.

You know how you can tell these laws working? By how much companies in the information-sharing business complain about them.

Your information is valuable. You shouldn’t just give it away, and you shouldn’t let third parties give it away without your consent. Imagine a world where if someone wants your personal information, they have to give you something tasty in return. [5]

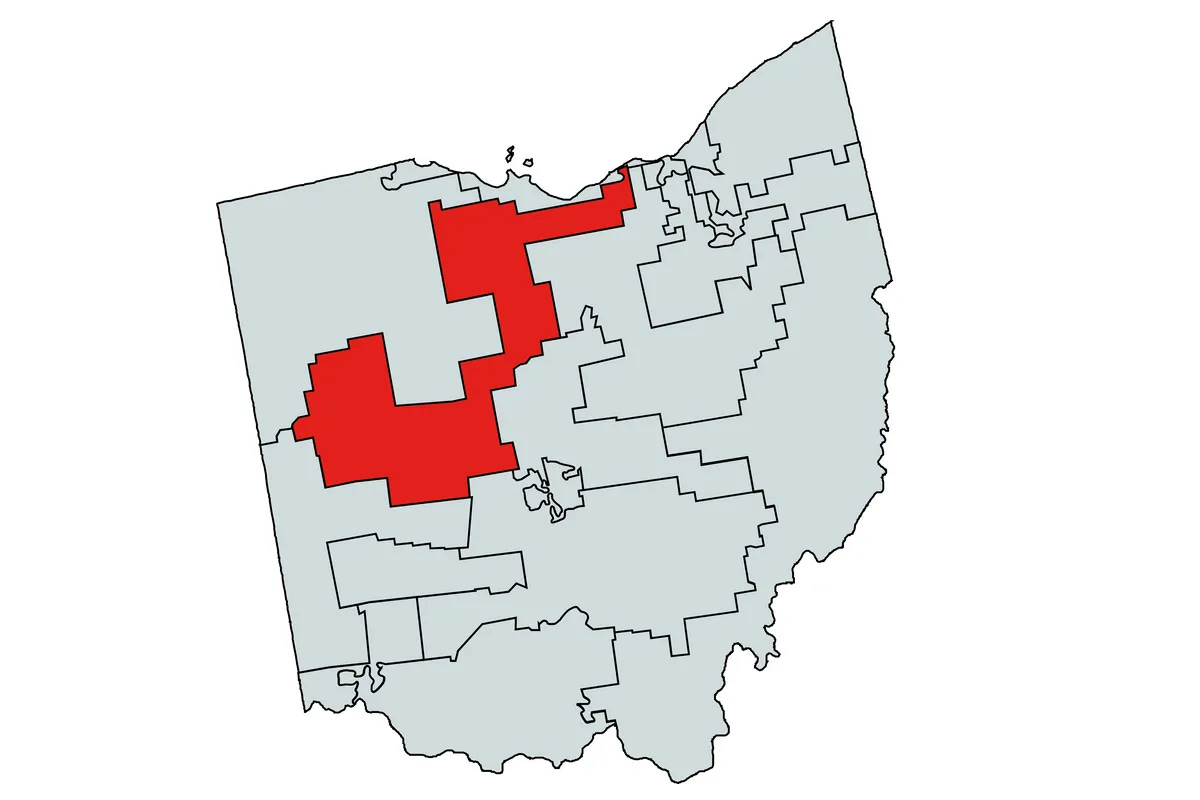

If it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, it’s probably Jim Jordan’s heavily gerrymandered Congressional district.

Now imagine a world where your political affiliations are unknown to the general public or to information brokers. Goodbye partisan gerrymandering. Also goodbye to those endless fundraising emails and texts.

AI that can infer information about you, without your actually revealing it, undermines your ability to control it. And AI built into surveillance cameras destroys our ability to move freely through the world without being watched.

These things are not inevitable. So rather than declare that you have ‘nothing to hide’, now is the time to say ‘It’s none of your goddamn business’.

What are your deepest darkest secrets? Reveal them in the comments below. (But only if you really want to.)

[1] Ironically, McNealy wrote an guest column for the Washington Post in 2001 titled “The Case Against Absolute Privacy,” in which he argues that people should be able to control who gets access to sensitive personal information like medical records – exactly what I argue above, and definitely more than zero.

[2] I did this purely as an experiment for this post. Then I asked for a refund. (Please don’t use these services; there are a million of them, all virtually identical; they all charge for information that’s available for free elsewhere, and they’re really annoying.)

[3] Those records would likely be public – and available for sale – but I’m not paying extra for that.

[4] You know who else has significantly higher than zero privacy? Corporations. There are all kinds of laws shielding the public from knowing who owns and operates private companies and off-shore LLCs. A little more transparency there would go a long way.

[5] A famous experiment by the University of Luxembourg found that nearly half of people approached by researchers were willing to gave up their social media passwords in exchange for a chocolate bar. But hey, at least they got a chocolate bar out of it.

I'm only going to tell you that I liked this piece. That's all I'm saying, so don't infer anything, OK?

Glad to see the reference to Kent Brockman, who, (as you probably don't remember) once ended a broadcast by announcing that he was leaving broadcasting to write a column called "You and Your Modem" for PC World.